Race and Representation in Afro-Cuba and Campus Life

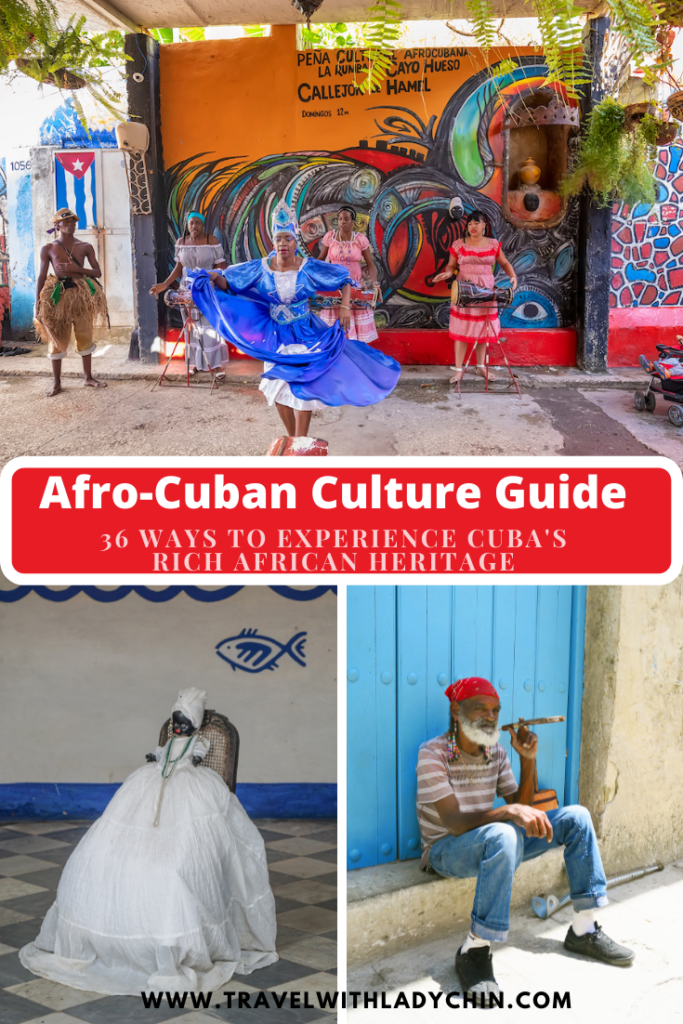

The Rumba performance in Havana’s streets showcases Afro-Cuban culture as a tourist attraction, which often strips it of its deeper cultural significance. In contrast, university dance rehearsals or celebrations of Afro-Cuban culture through dance represents a space where Afro-Cuban students can authentically engage with their heritage. Individuals such as Neri Torres, founder and executive/artistic director of IFE-ILE, a Miami-based nonprofit organization “dedicated to the preservation, promotion and advancement of Afro-Cuban culture through dance”, work to teach and spread her culture throughout the United States. This pair highlights the difference between cultural commodification and genuine cultural expression, reflecting themes from Clealand’s work and Campus Ecology Theory’s focus on the impact of environmental contexts on individual development.

Teacher in Cuban School vs. Cuban Service Worker

In Havana’s tourist zones, Afro-Cuban service workers are a highly visible part of Cuba’s international image. Their roles are essential to the country’s economy, especially in the post-Special Period era when tourism became a primary survival strategy. Yet as Danielle Clealand argues, this hyper-visibility is deeply racialized and economically constrained. Afro-Cubans are celebrated as cultural icons through music, dance, and hospitality, but are rarely granted authority or mobility beyond these performative roles. Their presence is valued when tied to the consumption and entertainment of others, rather than their intellectual or professional contributions. In contrast, Afro-Cuban representation within schools, particularly among teachers and administrators, remains limited. The classroom becomes a site where racial inequality is reinforced, not through blatant exclusion, but through structural absence. As Clealand notes, the ideology of racial democracy suppresses the discussion of race, which in turn erases the need to address underrepresentation in positions of educational authority.

Student Entrepreneurial Booth vs. Street Vendor

The street vendor embodies the informal economy that many Afro-Cubans rely on, often due to systemic barriers. The student entrepreneurial booth represents structured opportunities for innovation and business within academic settings. Such environments allow for a smooth path to career and socioeconomic success. This pair highlights disparities in access to economic opportunities, reflecting Clealand’s discussions on systemic inequality and Campus Ecology Theory’s focus on the role of institutional support in individual development.

Tourism Brochure and University Representation

The Cuban travel brochure sells a racially exoticized version of Cuba, where mixed-race femininity is aestheticized for global consumption and to drive tourism. In contrast, campus tours often center white narrators, even at diverse institutions. On the other hand, some institutions create the appearance that their student population and facility is diverse but in reality is not. This reinforces who is allowed to “represent” the institution. The pairing critiques who becomes the public face of a place, who is framed only as background or attraction, and the underlying reasons institutions or business sectors push such narratives.

Cuban Street Music vs. University Rehearsal

Afro-Cuban music fills Havana’s streets and tourist zones where it is celebrated as the pride of the nation. Street musicians are often central to Cuba’s cultural brand and featured in guidebooks, yet their labor exists outside formal recognition. Clealand describes how these traditions, while publicly celebrated, are systematically excluded from state-supported institutions like music conservatories and formal arts academies. Within those elite spaces, curricula and performance standards remain rooted in Eurocentric classical forms, and Afro-Cuban musical knowledge is often presented as informal rather than scholarship. These images show which forms of expression are granted legitimacy, and by who. The absence of Black students in rehearsal rooms, or their marginalization in Western environments, reflects how cultural practices are devalued when tied to Blackness, and only validated when reframed through whitened institutional filters.

Street Graffiti About Race and Campus Graffiti

As Clealand notes, when formal discourse denies racial inequality, Afro-Cubans turn to artistic expression and informal networks to express truth. Similarly, on a U.S. campus, graffiti can emerge anywhere on campus or protests can organized. These unsanctioned spaces become sites of protest when students feel that institutional channels fail them. Campus Ecology Theory shows that environments shape development through both explicit and hidden messages. When universities erase or downplay racial harm, they inadvertently reinforce silence. Graffiti or any form of expression can disrupt that silence. It becomes a counter-narrative, a call to see what’s often ignored. These images reveal that across political systems, marginalized voices often find visibility only in the margins, not on podiums or public spaces.

School Uniform vs. Embraced Expression

In Cuba, schoolchildren wear standardized uniforms symbolizing the nation’s commitment to equality and unity. This visual uniformity aligns with the state’s narrative of a raceless society, where discussions of racial identity are often suppressed. Clealand critiques this approach, highlighting how such policies can inadvertently erase the unique cultural identities of Afro-Cuban students, limiting their opportunities for self-expression within educational settings. Contrastingly, at Wesley College of Education in Ghana, Level 300 students recently showcased a vibrant cultural dance performance, adorned in traditional attire representing various Ghanaian ethnic groups. This event not only celebrated the nation’s rich cultural diversity but also provided students with a platform to express and embrace their individual and collective identities. The incorporation of indigenous dances and traditional clothing into the academic environment underscores the institution’s recognition and validation of cultural heritage as an integral component of education.

Cuban Protest and Campus Poster for DEI Initiative

In July 2021, thousands of Cubans took protested, voicing grievances over economic hardships, shortages of essential goods, and restrictions on civil liberties. These demonstrations were met with a heavy response from the government, including arrests and internet blackouts, highlighting the disconnect between the state’s proclaimed ideals and the lived realities of its citizens. Contrastingly, on many U.S. college campuses, DEI initiatives are prominently displayed through posters and campaigns. While these efforts aim to promote inclusivity, they often fall short of addressing systemic issues, sometimes serving more as symbolic gestures than catalysts for meaningful change. This shows a shared theme that the use of messaging to project a commitment to equality, which may mask underlying disparities. Both the Cuban government’s rhetoric and DEI campaigns can, intentionally or not, obscure the complexities of racial and social inequalities.

Afro-Cuban Grandmother vs. Campus Dining Hall Staff

In Cuba, the image of an Afro-Cuban grandmother preparing food in a kitchen captures the embedded role of racialized domestic labor. While care work is central to sustaining families and communities, it is often invisible and unrecognized within formal institutions. Clealand notes how, despite revolutionary claims of equality, Afro-Cuban women remain overrepresented in low-wage and informal labor sectors. Their roles are essential but framed as personal duty rather than professional expertise, reinforcing a historical pattern where Black women are relied on but rarely celebrated. This dynamic is also in U.S. university dining halls, where staff (who are represented fairly better) prepare and serve meals for students yet remain outside the intellectual and leadership spaces that define campus prestige. While students go through their day, few stop to consider the racial and economic hierarchies that make inequalities exist. Campus Ecology Theory asks us to pay attention to the micro-environments students pass through, such as who is visible, who is named, who is thanked. This exposes how care and intellect are divided along racial lines, and how institutional respect is often reserved for certain bodies over others.

Campus Newspaper Staff Photo vs. Cuban Newsstand (State-Controlled Media)

At a Cuban newsstand, rows of state-controlled newspapers and magazines feature political figures, cultural celebrations, and sanitized portraits of national life. What’s often absent, as Clealand emphasizes, are Afro-Cuban voices. This exclusion is not accidental; it reflects a broader pattern in Cuban media where racial discourse is avoided or framed as irrelevant under the revolutionary narrative of racial equality. Despite Afro-Cubans’ vital contributions to Cuban identity, they remain peripheral in the official record, reinforcing a racial democracy in which presence does not equal power. This marginalization is mirrored in the university setting. A university newspaper staff photo shows a predominantly white editorial team, which occurs all over the nation even at diverse institutions. While student journalists shape campus discourse, students of color often remain underrepresented in leadership roles, editorial decisions, or op-ed columns. Campus Ecology Theory who controls the tools of narrative-making within academic environments. This image pair reveals how media can reproduce structural silences. Who gets to write the headlines, choose the images, and decide what matters? Both Cuba and the universities exemplify representation without agency.